The Debt of Magic

My gran married young, and was widowed young, my current age. I have a very few regrets in life, but not getting to know grandpa is one of them. He was a great lover of nature, a working man with little spare time, escaping into the woods with binoculars and a camera whenever he could. A passion borne out by countless strips of film left behind. As I am getting older I too am drawn into the woods, increasingly not for ‘adventure’, but for the tranquility and the sense of awe it invariably brings. I sense we were kindred spirits, but I can only imagine, he died before my third birthday and I have no memories of him at all.

That in itself I find strange, for I have some very early memories. Hiding a hairbrush in the oven, not older than two, the commotion as it was ‘found’ (providing extra aroma for the Sunday roast). Sitting on a potty on the balcony of our new flat, not yet three, scaffolding all around, watching a cheery brickie in a red and black striped shirt at work (gone now, a scaffolding collapse some years later). Only just turned three, standing in front of the maternity hospital with my dad, waving, my sister just born.

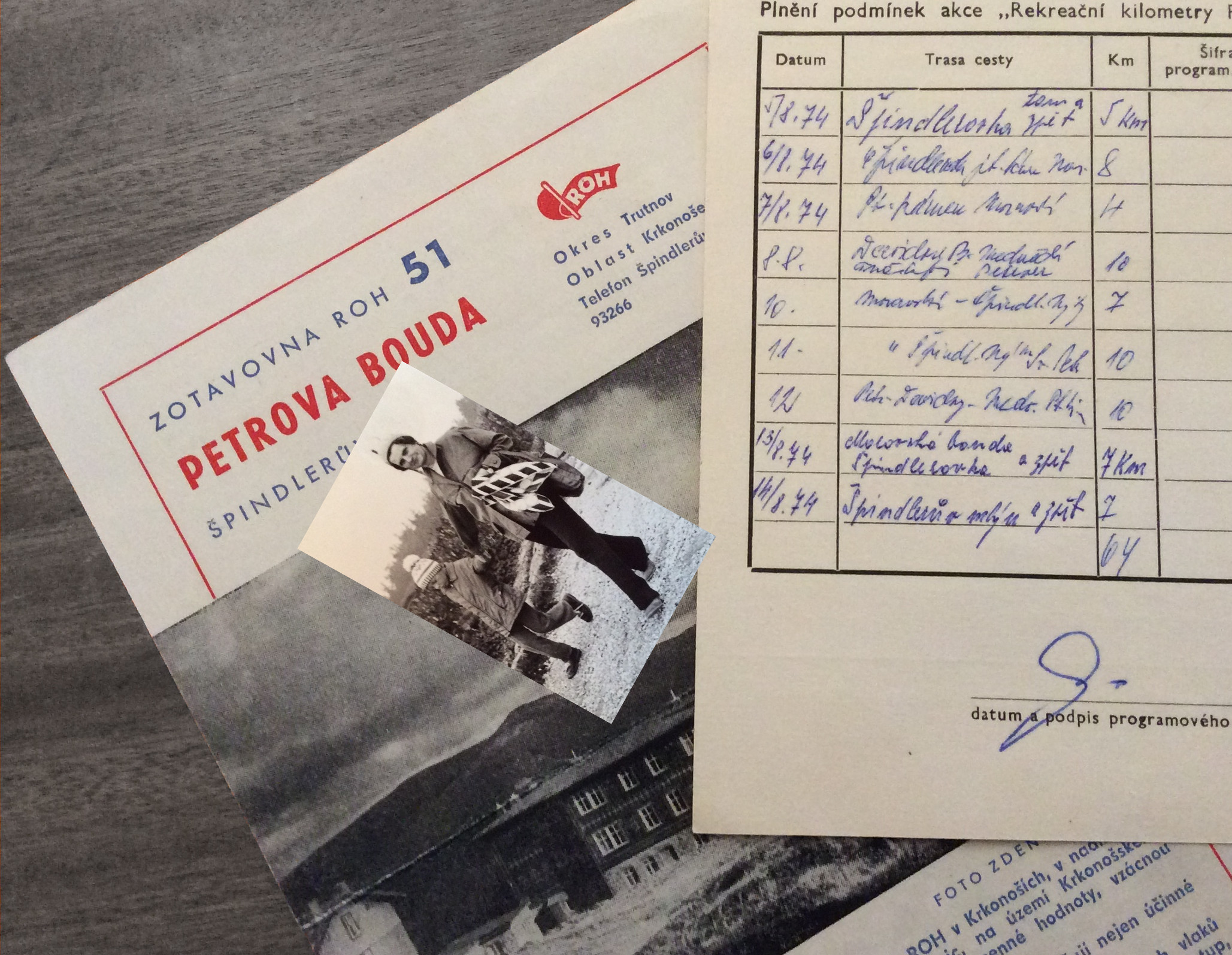

These are all genuine enough, but at the same time mere fragments, without context and continuity. My first real memories come from the summer after my fifth birthday: it’s August and my gran and I are going on a holiday in the Krkonoše mountains. A train, a bus, then a two hour hike to Petrova Bouda mountain refuge, our home for the next two weeks, wandering the hills, armed with a penknife and walking sticks gran fashioned out of some dead wood.

For me this was the time of many firsts. I learned my first (and only) German, ‘Nein, das ist meine!’, as my gran ripped out our sticks from the hands of a lederhosen-wearing laddie a few years older than me; he made the mistake of laying claim to them while we were browsing the inside of a souvenir shop (I often think somewhere in Germany is a middle aged man still having night terrors). It was the only time ever I heard my gran speaking German; she was fluent, but marked by the War (just as I am marked by my own history).

Up there in the hills I had my first encounter with the police state, squatting among the blaeberries, attending to sudden and necessary business, unfortunately, in the search for a modicum of privacy, on the wrong side of the border. The man in uniform, in spite of sporting a scorpion sub machine gun (the image of the large leather holster forever seared into my memory) stood no chance, and retreated hastily as gran rushed to the rescue. She was a formidable woman, and I was her oldest grandchild. Funnily enough, I was to have a similar experience a decade later in the Tatras, bivvying on the wrong side of the border only to wake up staring up the barrel of an AK-47, but that was all in the future then, though perhaps that future was already being shaped, little by little.

It was also the first time I drank from a mountain stream. A crystal clear water springing out of a miniature cave surrounded by bright green moss, right by the side of the path. Not a well known beauty spot sought after by many, but a barely noticeable trickle of water on the way to somewhere ‘more memorable’. We sat there having our lunch. Gran hollowed out the end bit of a bread stick to make a cup and told me a story about elves coming to drink there at night. We passed that spring several times during those days, and I was always hoping to catch a glimpse of that magical world. I still do, perhaps now more than ever.

Gran’s ventures into nature were unpretentious and uncomplicated: she came, usually on her old bicycle, she ate her sandwiches, and she saw. And I mean, really saw. Not just the superficially obvious, but the intricate interconnections of life, the true magic. One of her favourite places was a disused sand pit in a pine wood a few miles from where she lived. We spent many a summer day there picking cranberries and mushrooms, and then, while eating our pieces, watched the bees drinking from a tiny pool in the sand. Years later, newly married, I took Linda there, and I recall how, for the first time, I was struck by the sheer ordinariness of the place. Where did the magic go?

The magic is in the eye of the beholder. It is always there, it requires no superhuman abilities, no heroic deeds, no overpriced equipment. But seeing is an art, and a choice. It takes time developing, and a determination practicing. Gran was a seer, and she set me on the path of becoming one; I am, finally, beginning to make some progress.

In the years to come there were to be many more mountain streams. Times when the magic once only imagined by my younger self became real, tangible, perhaps even character-building. Times more intense, more memorable in the moment, piling on like cards, each on the top of the other, leaving just a corner here and corner there to be glimpsed beneath. The present consuming the past with the inevitability we call growing up.

Yet, ever so often it is worth pausing to browse through that card deck. There are moments when we stand at crossroads we are not seeing, embarking on a path that only comes into focus as time passes. Like a faint trace of a track on a hillside hard to see up close, but clearly visible from afar in the afternoon light, I can see now that my passion for the hills and my lifelong quest for the magic go back to the two weeks of a summer long gone in a place I have long since stopped calling home.

Gran passed away earlier this year. Among her papers was an A6 card, a hiking log from those two summer weeks. A laconic record of the first 64km of a life long journey she took me on; an IOU that shall remain outstanding.